I was just starting to write this blog when news came through that Claudio Ranieri had been sacked. Last year, against all odds (well, 5,000 to1), he led Leicester City to the Premier League title. His sacking is indeed the end of a fairytale.

Talking of fairytales, our national press have recently published articles on why UK farming will prosper without subsidies. They all quote the successful adaptation of NZ agriculture to a life without subsidies over the last 30 years. There are some elements of these articles with which I agree but others have a fairytale aspect about them.

There were bankruptcies in NZ when subsidies were first removed in the mid-1980s. Farmers who lost their businesses fell into two camps; those who lived the lifestyle but did not run a business and those really good farmers, especially younger farmers, who had invested heavily. Interest rates soared into the twenties at around the same time as subsidies were removed and there was no way out.

When I first visited NZ around 20 years ago, I was struck by the low level of capital investment in the less productive areas of the business, particularly in and around the farmstead i.e. no posh farmyards, farm tracks, grain storage and barns. However, there was investment going on in productive areas of the business, particularly irrigation. Farmers’ cars tended to be second-hand from Japan (who also drive on the left). Most farmers’ wives were in full time employment and/or heavily involved in the business. This was a vestige from the time when subsidies were first removed and a second income was often essential to keep the business ticking over.

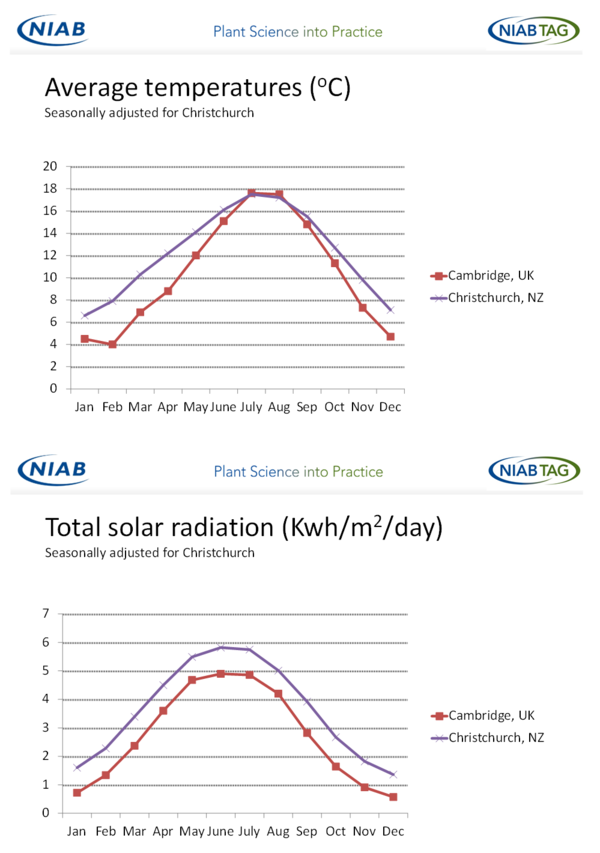

NZ has some climate and market advantages. The main arable area is the Canterbury Plains located to the west and south of Christchurch in the South Island. Here average monthly temperatures are higher than those in East Anglia except for the mid and late summer months. In addition, solar radiation is higher in NZ. This means that crop growth is potentially higher on the Canterbury Plains than in East Anglia, particularly in their autumn, winter and spring. The longer growing season in much of NZ particularly benefits grass production and we all know how they have exploited this to their advantage.

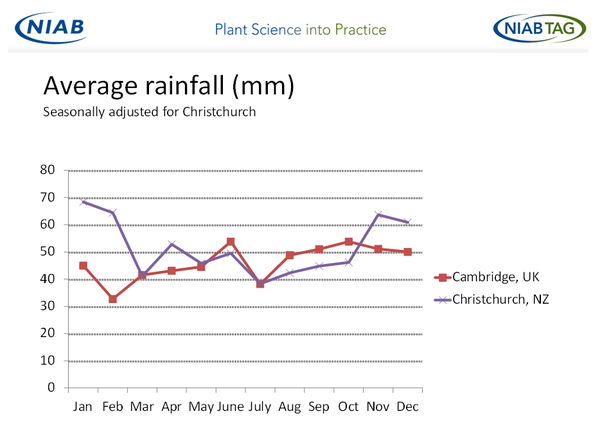

Average rainfall during the summer months on the Canterbury Plains is a little lower than here in Cambridge. Hence, things can get a bit dry in their summers, significantly limiting their higher potential yields. Many in NZ have overcome this by installing irrigation over the last thirty years or so, not only for arable production but also for grass. Initially there was little restriction in getting a licence for irrigation but things have tightened up significantly over the last 15 years and access to water is getting progressively more problematic. I would like to suggest that the extensive use of irrigation, with cheaper water, has been the major contributor to the increase in NZ productivity that our national press quote and laud. Unfortunately, such an extensive use of irrigation with relatively cheap water is not available to the UK grower.

On the Canterbury Plains it is not unusual for wheat to receive 100mm-125mm of irrigation a year. The average response is approaching 4 t/ha. The irrigation of wheat is not only a reflection of the cost of water but also the higher potential yields on the Canterbury Plains and that their wheat prices are higher. This is because NZ does not export cereals and so the price of any competing imported wheat has to include the transport costs to what is an isolated part of the world. This provides an advantage to the NZ grower of at least £10/t over world prices. The wheat price is currently around £170/t in NZ.

It is worth pointing out that wheat is often a break crop on the Canterbury Plains. Over the last 30 years NZ has done a great job in building up its herbage and clover seed production. In addition, irrigation has been a significant factor in enabling the establishment of a very significant area devoted to the production of small seeds for export, such as those for horticultural and forage crops. This diversity in cropping has enabled NZ farmers to continue to employ sensible rotations. Over the same period the herbage seed area in the UK has declined significantly and we are only now rediscovering the benefits of rotations.

An issue widely mentioned in our national press is that, without subsidies, our arable input costs, such as seeds, fertilisers and sprays, will go down. This may be a fairytale because, overall, these input costs are equivalent to those in NZ and have been throughout the time I have been visiting that country. Surprisingly, if anything, seed prices tend to be higher in NZ. Some NZ farmers say that their farm machinery costs more than ours but others disagree. This apparent contradiction may be partly due to the swings in exchange rates. Land costs appear to be approximately the same but there are few short term tenancy agreements in NZ.

Another fairytale element of the articles in our national press is the comment that UK farmers have not been keen to adopt new technology over the last thirty years because they have somehow been featherbedded. This, in my opinion, is a contemptuous slur. For instance, the rapid increase in the yields of NZ wheat over the last twenty years has been due to them adopting approaches that were established in the UK in the 1980s.

It is clear that NZ agriculture has not only survived the loss of subsidies but has emerged as a dynamic industry. Their arable industry has done this by exploiting their natural advantages, developing overseas markets and, sometimes, learning from others. I believe that our own industry is equally dynamic and hope that identifying and exploiting its natural advantages and expanding its market opportunities is sufficient for it to thrive in the future. A much more informative document on the impact of the removal of subsidies on NZ agriculture can be obtained by typing ‘farm subsidy reform dividends by Ralph Lattimore’ into your browser.