I did not write a blog last July predicting winter wheat yields. This was because I was busy doing other things but mainly because I copped out!

Predicting yields is a fool’s game as there are so many influencing factors and last year was particularly difficult for forecasting. This is why plant physiologists avoid putting their head on the block because they know that their often far too simplistic models do not fully cut the mustard. However, I mused at the time that English yields would be above average.

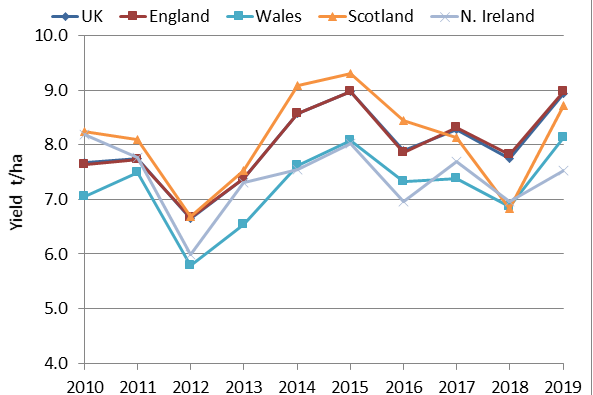

Defra issued its final estimates just before Christmas. These show that, in fact, the UK and English average yields matched the record average yields recorded in 2015 (first graph).

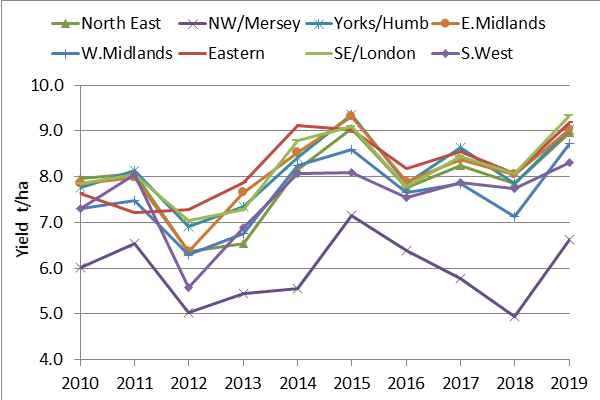

There may have been record average yields in some regions of England. However, it has to be borne in mind that there are errors in the estimates and these are usually higher than the difference between 2015 and 2019 regional yields (second graph). The only significant differences are that the average 2019 yields in Yorkshire and Humberside and the East Midlands are below those in 2015.

What was the explanation for such high yields in 2018/2019 winter wheat crop? Well it is difficult to be conclusive. Overall, in the main wheat producing areas of England, the winter/early spring was dry and it is unlikely that much or any waterlogging took place. The winter/early spring was also particularly warm and sunny. Hence, overwinter growth was good and lots of solar energy was intercepted. It is interesting that the foundation of the high yields in 2015 was that the crop entered the summer in great condition.

April and May 2019 experienced around average temperatures and so the crop did not race through its growth stages; this would have encouraged high grain numbers. June experienced average to slightly warmer than average temperatures and so the length of grain fill was around typical values. June also saw good levels of much needed rainfall. It is assumed that the general weather pattern experienced by the 2018/2019 winter wheat crop more than compensated for the only near average levels of sunshine in the critical months of May and June. The dry, warm and sunny winter perhaps explains why drilling as late as mid-November did not result in a significant yield penalty. It may not be the same in more typical years.

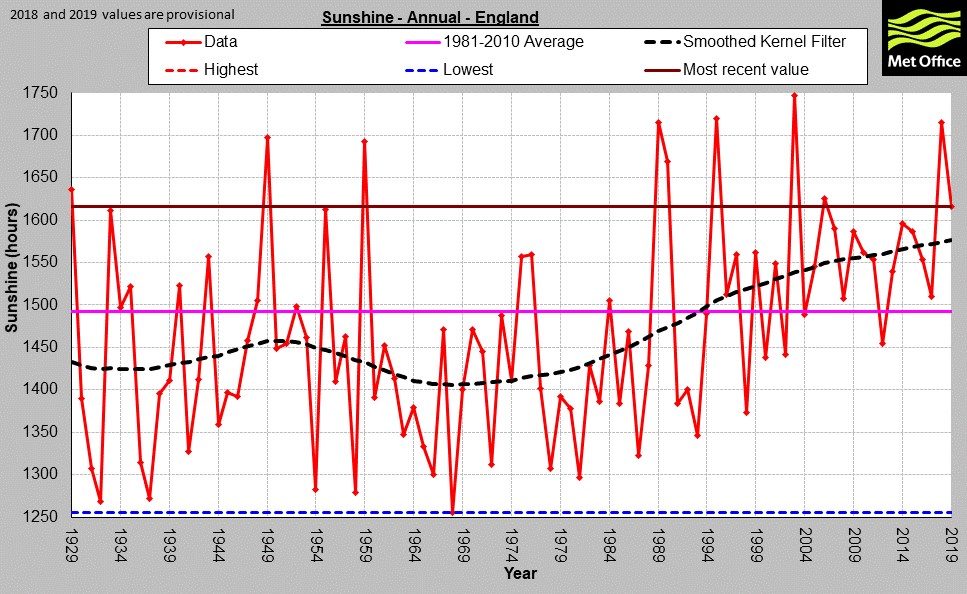

As a matter of interest, I discovered the graph below on the Met. Office website. It seems that there is a current trend for our weather to be sunnier, particularly in the winter and spring. Based on the yields in 2015 and 2019, that is good news.

2020 harvest prospects

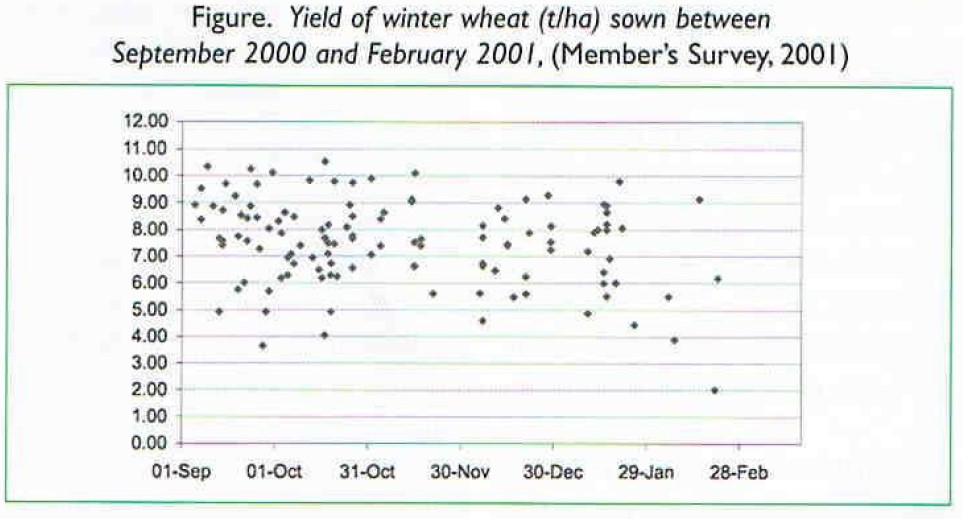

Prospects for the 2020 harvest do not, to say the least, look propitious. It has been appallingly wet and much of the significantly reduced area of winter wheat has been established late and in less than ideal soil conditions. It reminds me of the autumn of 2000 although then it was a bit drier in December than in this crop year; also, frosts enabled some drilling in January 2001.

NIAB/TAG conducted a survey of yields and drilling date in East Anglia that year and the results are provided in the (poor quality) graph below. There was a relatively small reduction in yield from very delayed drilling. This is hard to explain but maybe the earlier drilled crops experienced longer periods of waterlogging? The most common comment from the farmers taking part in the survey was that they wished that they had waited for better soil conditions before they drilled. However, it should be noted that the weather in 2001 from mid-April onwards was good for winter wheat.

Lessons from 2000/2001

To head off the inevitable sales onslaught this year we learnt (yet again!) that in the 2000/2001 season the early application of growth regulators did not increase tillers nor yields at all in the thin late drilled crops and there was no additional micronutrients deficiencies noted. There was the opportunity to save a bit on fungicides in the late drilled winter wheat crops but nitrogen requirements were about the same as usual. What was most memorable in 2001 was, for the first time, the widespread need to apply sulphur to cereals. That day was inevitably coming soon in any case with the then ever falling levels of sulphur deposition but the very heavy autumn and winter rainfall must have reduced soil reserves. 2020 will certainly not be a year to even consider cutting back on sulphur applications and RB 209 suggests that it is a year with an increased risk of deficiency.