- About

-

Research

- Agronomy and farming systems

-

Agricultural crop research

-

Research projects - agriculture

- About SASSA-SAI

- BioBoost

- Biomass Connect

- CTP for Sustainable Agricultural Innovation

- Climate Ready Beans - workshop presentations (March 2022)

- Crop diversity HPC cluster

- Designing Future Wheat

- Final project workshop

- Get involved

- List of materials

- News and updates

- Partners

- Rustwatch

- The Sentinel Crop Disease Surveillance Network

- The research team

- UK Cereal Pathogen Virulence Survey

- UK wheat varieties pedigree

- Weed management - IWM Praise

- Crop breeding

- Crop characterisation

- Data sciences

- Genetics and pre-breeding

- Plant biotechnology

- Plant pathology and entomology

- Resources

-

Research projects - agriculture

-

Horticultural crop research

-

Research projects - horticulture

- Augmented Berry Vision

- BEESPOKE

- Boosting brassica nutrition in smart growing systems

- CTP for Fruit Crop Research

- Develop user-friendly nutrient demand models

- Egg laying deterrents for spotted wing drosophila

- Enhancing the nutritional quality of tomatoes

- Improving berry harvest forecasts and productivity

- Improving vineyard soil health through groundcover management

- Intelligent growing systems

- Knowledge transfer for sustainable water use

- POME: Precision Orchard Management for Environment

- RASCAL

- STOP-SPOT

- UV-Robot

- Crop science and production systems

- Genetics, genomics and breeding

- Pest and pathogen ecology

- Field vegetables and salad crops

- Plum Demonstration Centre

- The WET Centre

- Viticulture and Oenology

-

Research projects - horticulture

- Crop Science Centre

- Research Projects

-

Services

- Analytical Services

- Business Development

- Commercial trial services

- Membership

- Plant breeding

- Plant characterisation

- Seed certification

-

Training

-

Technical agronomy training

- Advanced crop management of bulb onions

- Advanced crop management of vegetable brassicas

- Advanced nutrient management for combinable crops

- Benefits of cover crops in arable systems

- Best practice agronomy for cereals and oilseed rape

- Developing a Successful Strategy for Spring Crops

- Disease Management and Control in Cereal Crops

- Incorporating SFI options into your rotation

- Protected Environment Horticulture – Best Practice

- Techniques for better pest management in combinable crops

- Crop inspector and seed certification

- Licensed seed sampling

-

Technical agronomy training

- News & Views

- Events

-

Knowledge Hub

- Alternative and break crops

-

Crop genetics

- POSTER: Diversity enriched wheat (2025)

- POSTER: Genetics of wheat flag leaf size (2024)

- POSTER: Wheat yield stability (2024)

- Poster: Traits for future cereal crops (2022)

- POSTER: wild wheat fragment lines (2022)

- POSTER: Improving phenotyping in crop research (2022)

- PRESENTATION: Plant breeding for regen ag

- Poster: Designing Future Wheat (2020)

- Crop nutrition

-

Crop protection

- POSTER: Understanding the hierarchy of black-grass control (2025)

- POSTER: Emerging weed threats (2025)

- POSTER: Disease control in barley (2025)

- Poster: Weed seed predation in regen-ag (2024)

- POSTER: Disease control in winter wheat (2025)

- POSTER: Mode of action (2023)

- POSTER: Inter-row cultivation for black-grass control (2022)

- POSTER: UKCPVS winter wheat yellow rust in spring 2025 (2025)

- Poster: Management of Italian ryegrass (2021)

- POSTER: UKCPVS winter wheat rusts - 2024/25 review (2025)

- POSTER: UKCPVS disease monitoring and the benefit to UK growers (2025)

- POSTER: Diagnosing and scoring crop disease using AI (2025)

- POSTER: Finding new sources of Septoria resistance (2024)

- POSTER: Fungicide resistance research (2024)

- POSTER: Detecting air-borne pathogens (2024)

- POSTER: Oilseed rape diseases (2024)

- POSTER: Fungicide resistance research (2024)

- POSTER: Improving chocolate spot resistance (2022)

- Poster: Pathogen diagnostics (2022)

- Fruit

- Regen-ag & sustainability

-

Seed certification

- POSTER: Wheat DUS (2024)

- POSTER: Innovation in variety testing (2024)

- POSTER: AI and molecular markers for soft fruit (2024)

- POSTER: Barley crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Herbage grass crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Herbage legume crop identification (2024)

- POSTER: Minor cereal crop inspecting (2023)

- POSTER: Pulse crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Wheat crop identification (2023)

-

Soils and farming systems

- POSTER: Checking soil health - across space and time (2024)

- POSTER: Checking soil health - step by step (2024)

- POSTERS: Changing soil management practices (2022)

- Poster: Monitoring natural enemies & pollinators (2021)

- POSTER: Soil structure and organic matter (2024)

- POSTER: Novel wheat genotypes for regen-ag (2024)

- Video: New Farming Systems project (2021)

- Video: Saxmundham Experimental Site (2021)

- POSTER: Impact of prolonged rainfall on soil structure (2024)

- POSTER: Soil & agronomic monitoring study (2024)

- POSTER: The impact of rotations & cultivations (2024)

- VIDEO: Great Soils; soil sampling guidelines (2020)

- Poster: Soil invertebrates within arable rotations (2024)

- VIDEO: Soil health assessment (2021)

- POSTER: Saxmundham - modern P management learnings

- POSTER: Saxmundham - 125 years of phosphorus management

- Poster: Soil phosphorus - availability, uptake and management (2025)

- POSTER: Morley long term experiments (2025)

- POSTER: Exploiting novel wheat genotypes for regen-ag (2025)

- Video: Saxmundham Experimental Site (2021)

- Varieties

Redesigning lowland peat landscapes with farmers

In the second of our blog posts focusing on peatlands, NIAB's Elizabeth Stockdale and Megan Hudson from Fenland Soil explain how a new project in the Cambridgeshire Fens is looking to unlock farmers' local knowledge in managing peatlands sustainably...

The farming community is a vast repository of practical, in-depth knowledge of soils and land-management and these data are at a far higher resolution than most national datasets on which research and policy are based.

In the UK, local knowledge of landscape and soils (LSK) has rarely been a core component of soil assessment or land management policy. LSK is defined as “the knowledge of soil properties and management possessed by people living in a particular environment for some period of time”.

However, mounting evidence shows: i) the value of LSK integration into participatory soil surveys; and ii) exclusion of LSK often results in the failure of scientific interventions to improve land use, especially where scientific data are lacking.

The failure to exploit local knowledge has been recognised as a barrier to the achievement of the England Peat Strategy. In early 2022, NIAB and Fenland SOIL were awarded a £96,000 Natural England Peatland Restoration Discovery Grant to assess the feasibility of bring together the informal, fragmentary, and descriptive knowledge of land managers to show how this information can be brought together with that of other experts to help to address the challenge of unsustainable management and carbon loss in the Fens.

The aim of the work was to unlock barriers to rewetting and restoration by co-creating an integrated evidence base and developing Opportunities Maps at the local scale with the stakeholders, who will manage the resulting land-use or landmanagement change in practice mainly farmers and Internal Drainage Boards (IDBs).

Figure 1. Discovery Group farmers exploring the watery ecosystem of Fens ditches

Lowland peat systems are commonly a mix of peat soils of various depths with associated organo-mineral soils and hence a mosaic of management options is very likely to be needed to achieve effective long-term rewetting at catchment-scale. Any peatland restoration, with full and maintained rewetting, will need to be integrated effectively into catchments with other changes in land management practices.

These actions require close co-operation between water and land managers at local scales; in addition, much can be learned across farms and IDBs and hence a common methodology is needed to allow peer-peer and peer-expert reflection and learning between IDBs.

Hydrology is key to changing the land management practices of lowland drained peats to reduce emissions. Therefore, this methodology is designed to be deployed over whole hydrological units and therefore should be done across either an internal drainage board or a river catchment area. We identified three IDBs, covering just over 11,000 ha, within Cambridgeshire as pilot areas to develop and test the approach.

The Project took a mapping-led approach as a mechanism, initially for showing and sharing different views and then as a way of assembling, relating, revealing, sifting and speculating about land-water relationships, their interactions with biodiversity and the historic environment and the functions of restored peatland within these specific Fenland catchments.

The project worked closely with farmers and land managers in the three drainage boards in the pilot area and, in addition to carrying out the mapping process, also delivered training on soil identification, biodiversity and use of survey kit such as soil augers and pH meters (Figures 1 and 2). This local information was brought together with expertise on mapping peat soils, water management, agriculture, local heritage and biodiversity-led peatland management.

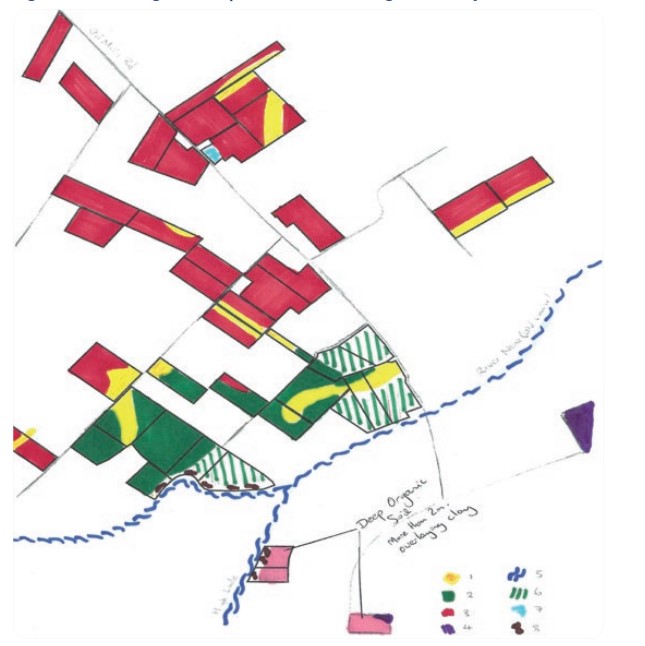

Farmer-led mapping approaches were used to provide field-scale maps of the existing extent of peat soils, together with ground-truthing for condition and depth. A group of pilot farmers had worked together to develop a common lexicon to describe the range of soils across their farms (see box for examples). This was used as the basis for farmer maps (often using felt-tip pens on existing farm maps; e.g. Figure 3); these were transferred to provide an underlying GIS soils layer.

Figure 2. Discovery Group farmers exploring Wicken Fen

By working with a local group of farming experts, but from outside the specific IDBs to ensure independence, it was possible to agree metrics that could be rapidly collated to give productivity indicators relevant to the cropping systems in the area of study. This approach was applied at field/field zone scale to link farmers’ knowledge of constraints to production and productivity, and then used spatial integration approaches to provide integrated field-scale maps of land-use productivity.

Farmers used simple keys to score fields or field zones in terms of several productivity factors including: yield potential for a reference crop (here winter wheat); flexibility (range of crops that can be grown); resilience; and soil variability. These data were combined to give a qualitative productivity index and no individual data were shared. In IDB workshops farmers discussed and peer reviewed their inputs.

Many agronomists, other farm advisors and some policymakers, began engagement with the project team with a very poor understanding of the landscape history, current approaches to land and water management and the scale and scope of the changes needed within the Fens landscape to deliver GHG mitigation.

Much of the discourse began with an assumption that approaches taken in the uplands (for peat restoration) and/or on mineral soils (e.g. land use change from cropping to grassland/woodland; regenerative practice in cropping systems) could be transferred simply and deliver GHG mitigation in these lowland peat systems.

Figure 3. A working farm map with soils knowledge added by the farmer

The project focused on creating and building understanding at the local scale within IDB working groups.

Farmers were actively engaged with the processes. Partner farmers encouraged others within the IDB to attend meetings and engage with the project (Figure 4) with a high success rate finally achieved (around 80% of all the land in the districts, with the majority of land not engaged in the project being mineral soils on the edge of The Fens area adjoining the Brecklands).

All farmers proved to be excellent informants. For soil/peat mapping there had been some concern raised in advance by the specialists that these data would be weak and not well aligned with the specialist description, classification and mapping approaches deployed in formal surveys.

However, on review of the outputs, the experts concurred that the spatial detail of farmer mapping was excellent and well-aligned with existing mapping (where available) at 1:63,360 or 1:50,000 scale. Overall, it was agreed that the farmer-collated soil information gave useful scoping data that could be used to guide targeted ground-truthing (with expert soil description as appropriate) to support mapping verification or land-use planning.

We had expected to be able to draw on IDB waterway maps and modelling of water-levels, to provide a baseline hydrology layer. We had also planned to use the IDB Biodiversity Action Plans developed by the IDBs with on-farm management options for biodiversity to create catchment habitat and habitat potential maps. However, the information held for hydrology and biodiversity at field or smaller-scale within IDBs was more sparse and less spatially explicit than had been anticipated.

A hydrology map was created by bringing together farmer knowledge of water levels and opportunities for water management at field scale with qualitative data drawn from local IDB expertise.

Figure 4. Farmers and experts discuss and annotate the Opportunity Maps

In all IDBs, discussion workshops to review the integrated opportunity maps identified how changes to IDB- and more local-scale water management could be made to allow landscape regeneration and rewetting. Within these drained catchments in the lowland peat landscape of the Fens, it rapidly became clear that the main limiting factor to any peatland restoration or rewetting is local-scale water management (together with associated costs of capital works and ongoing running cost).

The requirement for co-operative working to make changes to water levels is built into IDBs. Within the IDBs a general principle is that water levels cannot be changed to benefit a particular landowner, if that change will disadvantage other landowners.

This means that to make changes to water levels, landowners be able to isolate their land effectively from other land within the drainage district (this is relatively rare with <5% of the land area in the project IDBs falling into this category) or landowners need to work co-operatively with one another and the IDB engineers.

As rewetting has the potential to impact proximate infrastructure (roads, rail, power etc), especially if taking place at large (>100 ha) scale, it is important to identify and then engage with the relevant providers at an early stage of the conversation. There is currently no simple mechanism in place to identify or facilitate the key routes for engagement with such infrastructure providers.

This process was deliberately roots upwards, other approaches we are aware of are much more technical, desk-top and theory-based. We recognise that both approaches will often be needed as part of a collaborative process but this project has shown that where the specialist input supports a locally-led process, engagement is very effective and that this is more likely to support development of the long-term relationships needed to underpin practical change.

This approach is already being adopted with other lowland peat stakeholders in the UK and in peatland landscapes in Europe to adopt and locally adapt the opportunity mapping approach for farmer engagement as part of rewetting and restoration projects. In other landscapes we believe that similar approaches could help support land use and land management change.

The next steps

During the delivery of this project, Defra reviewed and changed the structure of ELMS, re-invigorating Countryside Stewardship to replace the planned Local Nature Recovery scheme. Countryside Stewardship now includes new rewetting options for lowland peat. Farmer feedback indicated this local scale action is favoured by the farmers in comparison with a full ecological restoration.

Farmer feedback indicated that local scale action for small areas within the IDBs where water tables are already high or the fields are easily hydrologically isolated will be considered for rewetting by integration into farm led Countryside Stewardship schemes.

Farmers also recognise the potential value of the large-scale Landscape Recovery scheme for land use changes of the scale that is envisaged in the Fens; however, they do not have the capacity working alone to catalyse such proposals.

Success in obtaining funding for this project was one of the factors which has led to the creation of the Fenland SOIL farmer-led organisation (from its origin within the CPICC Fenland Peat Committee) to proactively tackle

During the project, in October 2022, Anglian Water and Cambridge Water launched the first formal consultation associated with the proposed development of a new Fens Reservoir. This lies just outside the boundary of one IDB within the project but may provide some contemporaneous development in water management infrastructure to facilitate landscape regeneration in the IDB.

Farmers within the IDB will work together with Fenland SOIL to explore opportunities for ELMS Landscape Recovery or similar approaches to be used to leverage investment in water management structures for the reservoir to support wider rewetting and landscape regeneration approaches.

This article originally appeared in the Autumn 2023 edition of NIAB’s Landmark magazine. Landmark features in-depth technical articles on all aspects of NIAB crop research, comment and advice. You can sign up for free and get Landmark delivered to your door or inbox: