- About

-

Research

- Agronomy and farming systems

-

Agricultural crop research

-

Research projects - agriculture

- About SASSA-SAI

- BioBoost

- Biomass Connect

- CTP for Sustainable Agricultural Innovation

- Climate Ready Beans - workshop presentations (March 2022)

- Crop diversity HPC cluster

- Final project workshop

- Get involved

- List of materials

- News and updates

- Partners

- The Sentinel Crop Disease Surveillance Network

- The research team

- UK Cereal Pathogen Virulence Survey

- UK wheat varieties pedigree

- Weed management - IWM Praise

- Crop breeding

- Crop characterisation

- Data sciences

- Genetics and pre-breeding

- Plant biotechnology

- Plant pathology and entomology

- Resources

-

Research projects - agriculture

- Horticultural crop research

- Crop Science Centre

- Research Projects

- Research Publications

-

Services

- Analytical Services

- Business Development

- Commercial trial services

- Membership

- Plant breeding

- Plant characterisation

- Seed certification

-

Training

-

Technical agronomy training

- Advanced crop management of bulb onions

- Advanced crop management of vegetable brassicas

- Advanced nutrient management for combinable crops

- Benefits of cover crops in arable systems

- Best practice agronomy for cereals and oilseed rape

- Developing a Successful Strategy for Spring Crops

- Disease Management and Control in Cereal Crops

- Incorporating SFI options into your rotation

- Protected Environment Horticulture – Best Practice

- Techniques for better pest management in combinable crops

- Crop inspector and seed certification

- Licensed seed sampling

-

Technical agronomy training

- News & Views

- Events

-

Knowledge Hub

- Alternative and break crops

-

Crop genetics

- POSTER: Diversity enriched wheat (2025)

- POSTER: Genetics of wheat flag leaf size (2024)

- POSTER: Wheat yield stability (2024)

- Poster: Traits for future cereal crops (2022)

- POSTER: wild wheat fragment lines (2022)

- POSTER: Improving phenotyping in crop research (2022)

- PRESENTATION: Plant breeding for regen ag

- Poster: Designing Future Wheat (2020)

- Crop nutrition

-

Crop protection

- POSTER: Understanding the hierarchy of black-grass control (2025)

- POSTER: Emerging weed threats (2025)

- POSTER: Disease control in barley (2025)

- Poster: Weed seed predation in regen-ag (2024)

- POSTER: Disease control in winter wheat (2025)

- POSTER: Mode of action (2023)

- POSTER: Inter-row cultivation for black-grass control (2022)

- POSTER: UKCPVS winter wheat yellow rust in spring 2025 (2025)

- Poster: Management of Italian ryegrass (2021)

- POSTER: UKCPVS winter wheat rusts - 2024/25 review (2025)

- POSTER: UKCPVS disease monitoring and the benefit to UK growers (2025)

- POSTER: Diagnosing and scoring crop disease using AI (2025)

- POSTER: Finding new sources of Septoria resistance (2024)

- POSTER: Fungicide resistance research (2024)

- POSTER: Detecting air-borne pathogens (2024)

- POSTER: Oilseed rape diseases (2024)

- POSTER: Fungicide resistance research (2024)

- POSTER: Improving chocolate spot resistance (2022)

- Poster: Pathogen diagnostics (2022)

- Fruit

- Regen-ag & sustainability

-

Seed certification

- POSTER: Wheat DUS (2024)

- POSTER: Innovation in variety testing (2024)

- POSTER: AI and molecular markers for soft fruit (2024)

- POSTER: Barley crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Herbage grass crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Herbage legume crop identification (2024)

- POSTER: Minor cereal crop inspecting (2023)

- POSTER: Pulse crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Wheat crop identification (2023)

-

Soils and farming systems

- POSTER: Checking soil health - across space and time (2024)

- POSTER: Checking soil health - step by step (2024)

- POSTERS: Changing soil management practices (2022)

- Poster: Monitoring natural enemies & pollinators (2021)

- POSTER: Soil structure and organic matter (2024)

- POSTER: Novel wheat genotypes for regen-ag (2024)

- Video: New Farming Systems project (2021)

- Video: Saxmundham Experimental Site (2021)

- POSTER: Impact of prolonged rainfall on soil structure (2024)

- POSTER: Soil & agronomic monitoring study (2024)

- POSTER: The impact of rotations & cultivations (2024)

- VIDEO: Great Soils; soil sampling guidelines (2020)

- Poster: Soil invertebrates within arable rotations (2024)

- VIDEO: Soil health assessment (2021)

- POSTER: Saxmundham - modern P management learnings

- POSTER: Saxmundham - 125 years of phosphorus management

- Poster: Soil phosphorus - availability, uptake and management (2025)

- POSTER: Morley long term experiments (2025)

- POSTER: Exploiting novel wheat genotypes for regen-ag (2025)

- Video: Saxmundham Experimental Site (2021)

- Varieties

Orson's Oracle: Taking the pledge

Defra has published its consultation document on the ‘revised National Action Plan for the sustainable use of pesticides (plant protection products)’. It is not an exciting read but an important one and proves, yet again, that inevitably everyone and every organisation lives in silos.

A wider perspective required

There is only a passing reference in the document to maintaining crop yields but plenty of references to biodiversity. This is despite the fact that the two are intrinsically linked.

Biodiversity, in terms of pesticides used in agriculture, primarily means farmland and aquatic biodiversity and not the wider diversity of heaths, woodlands and other natural habitats. There are also frequent references to farmland birds in the document but in historical terms many of these were only niche species associated with gaps in the natural woodland that once covered much of this country. This indicates that farmland bird numbers are associated with habitat availability. Personally, I really cannot understand why the Pesticide Forum includes farmland birds as an indicator of the environmental impact of pesticide use when other factors have more influence on their numbers.

It is hard to overstress the importance of high yields in maintaining wider diversity. Just before Christmas there was a research paper published, which yet again concluded that sustaining or increasing crop yields is a critical element in avoiding the loss of habitats and biodiversity globally. Among the authors were researchers from the Universities of Leeds and Oxford and the RSPB as well as overseas academics.

There is now general agreement amongst independently thinking academics that high yields are of prime importance for sustaining global biodiversity. In the UK, maintaining yields/ha means that only the current cultivated area is required to provide a vital level of food security as well as ‘making space for nature’. For instance, our high yields can facilitate some re-wilding to enable the wider aspects of biodiversity to be encouraged.

UK yields are also particularly important in maintaining global biodiversity. This is because we have been blessed with soils and a climate that can sustain high yields. The following very simplistic and crude calculation makes the point. The UK average wheat yield over the last few years is around 8.4 t/ha, compared to a world average of 3.4 t/ha (source: FAOstat) and we produce around 15 million tonnes of this key food source a year. A reduction in our output of only 1% would mean that, on average, an additional 44,000 hectares of wheat would need to be cultivated somewhere else in the world to maintain world supplies.

What I am definitely not saying is that yield is so paramount that farmland diversity or any risk to human health and the wider environment should be ignored. What I am saying is that there always needs to be a balanced debate including recognising the importance of high yields/ha to both UK and global biodiversity.

IPM – a more rounded view is a must

The consultation document is, understandably, very much focussed on how the industry can deliver integrated pest management (IPM). This it defines on page 14 of the document as ‘the combined use of all available control methods, including targeted use of pesticides used when alternatives are ineffective or unavailable’. Who could argue with that? What is not mentioned are the impacts of some of the alternatives to pesticides, their reliability and their cost. There should really be thorough risk assessments done on the impact of some of the alternatives to pesticides on human health and environmental goals.

For instance, meeting our carbon zero targets is mentioned a few times in the document. Yet there is implicit support for non-herbicidal weed control. Currently, mechanical weed control in its various guises is the most practical alternative method to herbicides for removing weeds post-emergence of crops. Mechanical methods, when compared to chemical methods, can increase carbon emissions and eutrophication, both through soil disturbance as well as tractor hours and fuel. Also, according to a report for the Danish Environment Protection Agency, they can negatively impact some soil surface fauna and have a very significant impact on ground-nesting birds.

Regular soil disturbance close to crop plants may also impact on the web of arbuscular mycorrhiza on their roots. Unfortunately, I cannot find any relevant study of this issue in the scientific literature. Perhaps the fact that herbicides can prevent the need for regular soil disturbance was behind the French Minister of Agriculture recently saying on television that ‘if there is no glyphosate, soil conservation can’t be done’. Just think of common couch control without glyphosate. The multiple and intense cultivations required would lead to a major decarbonising of the soil.

Government and regulators could do more

Missing from the consultation document are some of the regulatory changes that government could make to help facilitate IPM. It could approve the adoption, with any relevant safeguards, of gene editing to speed up the current methods for breeding more disease and insect resistant crops. It could also lead from the front by publishing a brief desk study on whether some withdrawn pesticides could possibly be re-introduced if used on only a small proportion of a field.

This would not only be a huge boost to the adoption of technologies that enable successful spatially targeted spraying but could also boost the management of pesticide resistance.

To its credit, the Chemical Regulation Division of HSE hinted at the recent BCPC Congress that it is contemplating a more holistic approach to the pesticide reviews process. This is a positive step for all sorts of reasons. About 20 years ago I was involved in a review of a number of nematicides. This was done one by one as the reports became available. This seemed a very cack-handed approach to me.

It could have led to individual nematicides failing re-registration one by one until there were just one or two left to review. The distinct danger was that the remaining ones could then provide an enhanced economic argument for their retention on the market, yet it may be that the lower risk alternatives had already been withdrawn. Similarly, rather than review individual pesticides to control a particular target, say aphicides, they need to be reviewed as a whole in order that the most acceptable environmental and resistance management outcomes are identified.

IPM is an attitude of mind

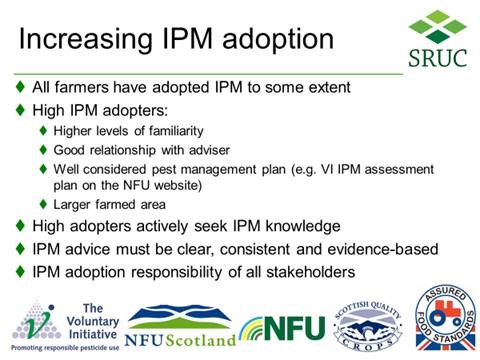

Much of the document is concerned with delivering IPM in practice. It must be said that all farmers are adopting IPM to some extent (the slide contains the conclusions of a survey of the UK and Ireland co-ordinated by Henry Creissen, SRUC). No farmer will knowingly spend money on a pesticide when it is not necessary or there is an effective, cheaper and easy to implement alternative. However, many farmers are demonstrating that a greater implementation of IPM is possible. These farmers are willing to put in the extra mile to seek out, refine and implement alternative options and are more willing to take on the additional financial risk of adopting non-pesticide control measures. These farmers demonstrate more than anything that increased IPM adoption is primarily an attitude of mind.

This slide is reproduced with permission from Henry Creissen

What is the way to increase adoption of IPM? Could it be as a result of an inspired initiative by Defra? I particularly like the following suggestion made by Tom Bradshaw of the NFU in a Voluntary Initiative meeting last year. He proposed getting individual farmers to pledge not to use insecticides at all in some specified crop types in return of a payment of, say, £25-£30/ha/annum.

There are an increasing number of farmers who do not now use any insecticides on broad acre crops and this incentive will reward them as well as inspire others to investigate the approaches to make it possible. To this end, this initiative should be backed up by a targeted knowledge exchange campaign. This could kick-start a wider adoption of enhanced IPM and so this pledge may only need to be supported by the taxpayer for a limited number of years.

Are pesticide reduction targets beneficial?

It is clear that pesticide reduction targets are intended in the longer term but it is not clear whether this reduction is in usage or, perhaps, a broader measure of impact. Defra is perhaps well-aware that reduction targets are a grenade that could go off in its hands. Whatever the reduction parameter, setting baselines and comparing annual pesticide usage or impact will be a nightmare because of the ever-changing weather conditions. For instance, the wet autumn of 2019 resulted in far fewer and later sown winter cereal crops, when compared to previous years, and resulted in a reduction in total pesticide usage in arable crops for the 2020 harvest year.

Government can also indirectly increase pesticide use, and perhaps also impact, by revoking the use of some pesticides. For instance, banning the use of neonic seed dressings in sugar beet has had to be replaced by two to three overall foliar insecticide sprays in an attempt to control beet yellows virus. Finally, reduction targets might encourage farmers to adopt some cultural practices that may inadvertently have a more detrimental impact on the environment and/or on human health.

Experience from Denmark shows that if farmers do not believe that the reduction targets are realistic and fair, they will just shrug their shoulders and not try too hard to achieve them. The ‘better to be hanged as a sheep than as a lamb’ mentality takes over.

What about thresholds?

Finally, the consultation document also seems to have a rather touching faith in the adoption of action thresholds. They are applicable to the control of some insects, but they are largely irrelevant for weed control. Want to know why? Perhaps that is the subject of a further blog . . . this one has gone on far too long!