- About

-

Research

- Agronomy and farming systems

-

Agricultural crop research

-

Research projects - agriculture

- About SASSA-SAI

- BioBoost

- Biomass Connect

- CTP for Sustainable Agricultural Innovation

- Climate Ready Beans - workshop presentations (March 2022)

- Crop diversity HPC cluster

- Designing Future Wheat

- Final project workshop

- Get involved

- List of materials

- News and updates

- Partners

- Rustwatch

- The Sentinel Crop Disease Surveillance Network

- The research team

- UK Cereal Pathogen Virulence Survey

- UK wheat varieties pedigree

- Weed management - IWM Praise

- Crop breeding

- Crop characterisation

- Data sciences

- Genetics and pre-breeding

- Plant biotechnology

- Plant pathology and entomology

- Resources

-

Research projects - agriculture

-

Horticultural crop research

-

Research projects - horticulture

- Augmented Berry Vision

- BEESPOKE

- Boosting brassica nutrition in smart growing systems

- CTP for Fruit Crop Research

- Develop user-friendly nutrient demand models

- Egg laying deterrents for spotted wing drosophila

- Enhancing the nutritional quality of tomatoes

- Improving berry harvest forecasts and productivity

- Improving vineyard soil health through groundcover management

- Intelligent growing systems

- Knowledge transfer for sustainable water use

- POME: Precision Orchard Management for Environment

- RASCAL

- STOP-SPOT

- UV-Robot

- Crop science and production systems

- Genetics, genomics and breeding

- Pest and pathogen ecology

- Field vegetables and salad crops

- Plum Demonstration Centre

- The WET Centre

- Viticulture and Oenology

-

Research projects - horticulture

- Crop Science Centre

-

Services

- Analytical Services

- Business Development

- Commercial trial services

- Membership

- Plant breeding

- Plant characterisation

- Seed certification

-

Training

-

Technical agronomy training

- Advanced crop management of bulb onions

- Advanced crop management of vegetable brassicas

- Advanced nutrient management for combinable crops

- Benefits of cover crops in arable systems

- Best practice agronomy for cereals and oilseed rape

- Developing a Successful Strategy for Spring Crops

- Disease Management and Control in Cereal Crops

- Incorporating SFI options into your rotation

- Protected Environment Horticulture – Best Practice

- Techniques for better pest management in combinable crops

- Crop inspector and seed certification

- Licensed seed sampling

-

Technical agronomy training

- News & Views

- Events

-

Knowledge Hub

- Alternative and break crops

-

Crop genetics

- POSTER: Diversity enriched wheat (2025)

- POSTER: Genetics of wheat flag leaf size (2024)

- POSTER: Wheat yield stability (2024)

- Poster: Traits for future cereal crops (2022)

- POSTER: wild wheat fragment lines (2022)

- POSTER: Improving phenotyping in crop research (2022)

- PRESENTATION: Plant breeding for regen ag

- Poster: Designing Future Wheat (2020)

- Crop nutrition

-

Crop protection

- POSTER: Understanding the hierarchy of black-grass control (2025)

- POSTER: Emerging weed threats (2025)

- POSTER: Disease control in barley (2025)

- Poster: Weed seed predation in regen-ag (2024)

- POSTER: Disease control in winter wheat (2025)

- POSTER: Mode of action (2023)

- POSTER: Inter-row cultivation for black-grass control (2022)

- POSTER: UKCPVS winter wheat yellow rust in spring 2025 (2025)

- Poster: Management of Italian ryegrass (2021)

- POSTER: UKCPVS winter wheat rusts - 2024/25 review (2025)

- POSTER: UKCPVS disease monitoring and the benefit to UK growers (2025)

- POSTER: Diagnosing and scoring crop disease using AI (2025)

- POSTER: Finding new sources of Septoria resistance (2024)

- POSTER: Fungicide resistance research (2024)

- POSTER: Detecting air-borne pathogens (2024)

- POSTER: Oilseed rape diseases (2024)

- POSTER: Fungicide resistance research (2024)

- POSTER: Improving chocolate spot resistance (2022)

- Poster: Pathogen diagnostics (2022)

- Fruit

- Regen-ag & sustainability

-

Seed certification

- POSTER: Wheat DUS (2024)

- POSTER: Innovation in variety testing (2024)

- POSTER: AI and molecular markers for soft fruit (2024)

- POSTER: Barley crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Herbage grass crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Herbage legume crop identification (2024)

- POSTER: Minor cereal crop inspecting (2023)

- POSTER: Pulse crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Wheat crop identification (2023)

-

Soils and farming systems

- POSTER: Checking soil health - across space and time (2024)

- POSTER: Checking soil health - step by step (2024)

- POSTERS: Changing soil management practices (2022)

- Poster: Monitoring natural enemies & pollinators (2021)

- POSTER: Soil structure and organic matter (2024)

- POSTER: Novel wheat genotypes for regen-ag (2024)

- Video: New Farming Systems project (2021)

- Video: Saxmundham Experimental Site (2021)

- POSTER: Impact of prolonged rainfall on soil structure (2024)

- POSTER: Soil & agronomic monitoring study (2024)

- POSTER: The impact of rotations & cultivations (2024)

- VIDEO: Great Soils; soil sampling guidelines (2020)

- Poster: Soil invertebrates within arable rotations (2024)

- VIDEO: Soil health assessment (2021)

- POSTER: Saxmundham - modern P management learnings

- POSTER: Saxmundham - 125 years of phosphorus management

- Poster: Soil phosphorus - availability, uptake and management (2025)

- POSTER: Morley long term experiments (2025)

- POSTER: Exploiting novel wheat genotypes for regen-ag (2025)

- Video: Saxmundham Experimental Site (2021)

- Varieties

- About

-

Research

- Agronomy and farming systems

-

Agricultural crop research

-

Research projects - agriculture

- About SASSA-SAI

- BioBoost

- Biomass Connect

- CTP for Sustainable Agricultural Innovation

- Climate Ready Beans - workshop presentations (March 2022)

- Crop diversity HPC cluster

- Designing Future Wheat

- Final project workshop

- Get involved

- List of materials

- News and updates

- Partners

- Rustwatch

- The Sentinel Crop Disease Surveillance Network

- The research team

- UK Cereal Pathogen Virulence Survey

- UK wheat varieties pedigree

- Weed management - IWM Praise

- Crop breeding

- Crop characterisation

- Data sciences

- Genetics and pre-breeding

- Plant biotechnology

- Plant pathology and entomology

- Resources

-

Research projects - agriculture

-

Horticultural crop research

-

Research projects - horticulture

- Augmented Berry Vision

- BEESPOKE

- Boosting brassica nutrition in smart growing systems

- CTP for Fruit Crop Research

- Develop user-friendly nutrient demand models

- Egg laying deterrents for spotted wing drosophila

- Enhancing the nutritional quality of tomatoes

- Improving berry harvest forecasts and productivity

- Improving vineyard soil health through groundcover management

- Intelligent growing systems

- Knowledge transfer for sustainable water use

- POME: Precision Orchard Management for Environment

- RASCAL

- STOP-SPOT

- UV-Robot

- Crop science and production systems

- Genetics, genomics and breeding

- Pest and pathogen ecology

- Field vegetables and salad crops

- Plum Demonstration Centre

- The WET Centre

- Viticulture and Oenology

-

Research projects - horticulture

- Crop Science Centre

-

Services

- Analytical Services

- Business Development

- Commercial trial services

- Membership

- Plant breeding

- Plant characterisation

- Seed certification

-

Training

-

Technical agronomy training

- Advanced crop management of bulb onions

- Advanced crop management of vegetable brassicas

- Advanced nutrient management for combinable crops

- Benefits of cover crops in arable systems

- Best practice agronomy for cereals and oilseed rape

- Developing a Successful Strategy for Spring Crops

- Disease Management and Control in Cereal Crops

- Incorporating SFI options into your rotation

- Protected Environment Horticulture – Best Practice

- Techniques for better pest management in combinable crops

- Crop inspector and seed certification

- Licensed seed sampling

-

Technical agronomy training

- News & Views

- Events

-

Knowledge Hub

- Alternative and break crops

-

Crop genetics

- POSTER: Diversity enriched wheat (2025)

- POSTER: Genetics of wheat flag leaf size (2024)

- POSTER: Wheat yield stability (2024)

- Poster: Traits for future cereal crops (2022)

- POSTER: wild wheat fragment lines (2022)

- POSTER: Improving phenotyping in crop research (2022)

- PRESENTATION: Plant breeding for regen ag

- Poster: Designing Future Wheat (2020)

- Crop nutrition

-

Crop protection

- POSTER: Understanding the hierarchy of black-grass control (2025)

- POSTER: Emerging weed threats (2025)

- POSTER: Disease control in barley (2025)

- Poster: Weed seed predation in regen-ag (2024)

- POSTER: Disease control in winter wheat (2025)

- POSTER: Mode of action (2023)

- POSTER: Inter-row cultivation for black-grass control (2022)

- POSTER: UKCPVS winter wheat yellow rust in spring 2025 (2025)

- Poster: Management of Italian ryegrass (2021)

- POSTER: UKCPVS winter wheat rusts - 2024/25 review (2025)

- POSTER: UKCPVS disease monitoring and the benefit to UK growers (2025)

- POSTER: Diagnosing and scoring crop disease using AI (2025)

- POSTER: Finding new sources of Septoria resistance (2024)

- POSTER: Fungicide resistance research (2024)

- POSTER: Detecting air-borne pathogens (2024)

- POSTER: Oilseed rape diseases (2024)

- POSTER: Fungicide resistance research (2024)

- POSTER: Improving chocolate spot resistance (2022)

- Poster: Pathogen diagnostics (2022)

- Fruit

- Regen-ag & sustainability

-

Seed certification

- POSTER: Wheat DUS (2024)

- POSTER: Innovation in variety testing (2024)

- POSTER: AI and molecular markers for soft fruit (2024)

- POSTER: Barley crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Herbage grass crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Herbage legume crop identification (2024)

- POSTER: Minor cereal crop inspecting (2023)

- POSTER: Pulse crop identification (2023)

- POSTER: Wheat crop identification (2023)

-

Soils and farming systems

- POSTER: Checking soil health - across space and time (2024)

- POSTER: Checking soil health - step by step (2024)

- POSTERS: Changing soil management practices (2022)

- Poster: Monitoring natural enemies & pollinators (2021)

- POSTER: Soil structure and organic matter (2024)

- POSTER: Novel wheat genotypes for regen-ag (2024)

- Video: New Farming Systems project (2021)

- Video: Saxmundham Experimental Site (2021)

- POSTER: Impact of prolonged rainfall on soil structure (2024)

- POSTER: Soil & agronomic monitoring study (2024)

- POSTER: The impact of rotations & cultivations (2024)

- VIDEO: Great Soils; soil sampling guidelines (2020)

- Poster: Soil invertebrates within arable rotations (2024)

- VIDEO: Soil health assessment (2021)

- POSTER: Saxmundham - modern P management learnings

- POSTER: Saxmundham - 125 years of phosphorus management

- Poster: Soil phosphorus - availability, uptake and management (2025)

- POSTER: Morley long term experiments (2025)

- POSTER: Exploiting novel wheat genotypes for regen-ag (2025)

- Video: Saxmundham Experimental Site (2021)

- Varieties

Boring Brits?

By

We went out for lunch last Saturday. The weather was glorious and all the tables in the garden were occupied, so unfortunately we had to sit inside. The conversation soon got around to managing risk when growing wheat in low rainfall areas of Australia. I was talking to a consultant who has been a major driver in the development of risk management strategies in such situations; we were having lunch in Bendigo, Victoria...in Australia.

Obviously, much of the risk management strategy revolves around water availability. Last year soils were full of moisture at sowing in early May (our October equivalent), but this year they could be bone dry. So how do Victoria’s farmers cope with this extreme variation, when typically rainfall after sowing could be insufficient to meet the full needs of the crop?

When I was first in Australia, around ten years ago, this was done by estimating how much water there was in the soil at the start of the season. Either a steel rod was pushed into the soil or a calculation was made based on the amount of post-harvest rainfall, providing a crude measure of how many mm of water was available at the time of sowing.

The assumption was for 20 kg of grain for each mm of moisture, and as rain fell during the season this was measured and the estimated yield as adjusted accordingly, with nitrogen (N) applied based on yield potential.

The issue with N is that there should be sufficient to achieve the anticipated yield. However, too much will mean excessive green leaf and water loss and as a result, reduction in both yield and grain size.

Now, computerised systems are used that require information at the start of the season based on a soil core analysis. Available moisture and N are measured and where prospects are good for yield and some additional N is justified this is applied in the combine drill.

As the season progresses the computer programme predicts N uptake and, based on any rainfall after sowing, expected yield. Additional N is applied if a shortage is predicted.

Water availability, along with plagues of mice and locusts, are not the only risks to take into account.

Sow too early and the risk of frost damage increases. Crops are grown through the winter and harvested in November (equivalent to our April) with the threat of wipeout due to frost at flowering. Sow too late and there is an increased prospect of yield damage from high temperatures during flowering.

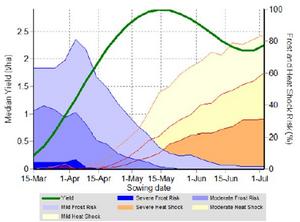

These risks can also be assessed by a computer programme based on weather records over the last 100 years. The image shows a printout for a specific variety at a specific location:

These risks can also be assessed by a computer programme based on weather records over the last 100 years. The image shows a printout for a specific variety at a specific location:

- potential yield according to sowing date is the thick line;

- the falling lines on the left are the decreasing risk of frost damage as sowing is delayed; and

- the increasing lines on the right are the increasing risk of heat damage as sowing is delayed.

The optimum date for sowing, assuming sufficient moisture for germination, is early May.

Doesn’t this make British wheat production sound boring?

Jim is on a study trip to Australia so expect further Oz-blogs over the coming weeks

Contact

Niab

Park Farm

Villa Road

Histon

Cambridge

CB24 9NZ, UK

Tel: +44(0)1223 342200

Email: [email protected]